Over the last year, financial uncertainty resulting from the Brexit referendum has seen the value of sterling fall steeply. Foreign exchange rate fluctuations are able to have an acute impact upon the Bhopal Medical Appeal because the charity converts significant amounts of sterling to Indian Rupees each year. At the time of writing, we’ve consequently lost almost a fifth of reserves built-up to support the crucial ongoing work of our clinics in Bhopal. And there’s no telling yet how much further sterling may decline over the coming months….

We last sent an urgent appeal almost five years ago. At that time the backwash from the 2008 banking crisis, as well as rocketing fuel, medicine and food prices in India, were combining to have a negative impact upon the reserves we hold – reserves that guarantee continuation of our work in Bhopal.

Your generosity laid the foundations for the achievements of the last five years. In 2012, Chingari had expanded its staff to be able to accept 120 children a day; thanks to you, that number has more than doubled. Most of the children joining Chingari find it difficult to even hold a pen at first: following dedicated care, 76 are now able to spend time attending normal schools.

The work being done in Bhopal is inspiring, but this is not the only reason that demand for our services increases year-on-year. Poisons continue to fan out from the derelict factory, reaching new wells and new wombs. Cancers are manifesting at levels wildly over standard rates. Over 1,700 children are identified with congenital abnormalities: Chingari has registered 850 children disabled by Carbide, but is able to care for less than a third of this need.

And at the same time, there is the impact of Brexit. Prior to the leave vote, one pound bought us 100 Rupees. The fall in the value of sterling since means that 18% of the reserves set aside for the clinics have so far been lost, and it may get worse yet

Indicators are that as Brexit negotiations proceed, the pound will continue to weaken. In anticipation, Sambhavna and Chingari are reducing costs. We are taking measures to limit our exposure to fluctuations in sterling, but to maintain our grants and services at the present level and ensure the clinics’ unique and precious work is not interrupted or threatened, we also need to replenish our reserves.

All of the work we do is almost entirely funded by you, our friends and supporters. There’s a simple, relatively painless way you can help. A modest regular donation would enable us to better forecast, plan our support programmes, and reduce admininstration costs – an inestimable help in these uncertain times.

Please consider making a regular donation.

You can set up a direct debit or make a single gift here: CLICK

The following letter to friends and supporters by the charity’s Executive Trustee, Tim Edwards, explains why the clinics in Bhopal are an inspiration to so many.

Dear friend,

If you happen to think of the year most recently passed in terms of two extraordinary events, please also consider the events I’m about to describe.

On September 2nd, 2016, Sambhavna Trust marked 20 years service in the care of people harmed by Union Carbide in Bhopal. Within a few days, Chingari Trust reached ten years working to rehabilitate the city’s damaged children. In a year of division and turmoil, three decades worth of humanity and hope. And were it not for you (and others like you), it could not have happened.

I was lucky to be in Bhopal for the celebrations. They brought back to me strong and affecting memories, and I hope you don’t mind if I take a few moments to share them.

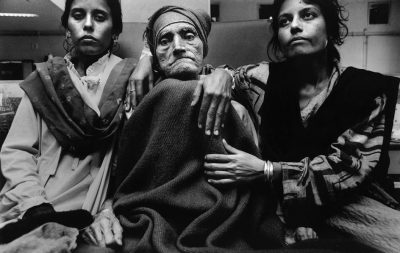

Sambhavna Clinic had been open for three years and was already an important part of local life when I first visited. Long queues formed early each morning in the unpaved road beside its entrance gate. After registering, visitors were seen by one of Sambhavna’s three doctors. Consultations and examinations happened as efficiently as due care and space allowed. In the narrow main corridor, and on stone benches in the cramped courtyard, people waited amiably for pathology results or dispensation of medicines. A short flight of steps up, yoga specialist Sushmita and panchakarma expert Alka offered drug-free therapies for chemically-burdened bodies.

The flood of visitors only began to relent by afternoon. As health workers returned from door-to-door work in nearby bastis (slums), staff would gather on the open roof to catch their breaths, share their lunches and swap stories by the shady branches of a tall mango tree.

The dedication of this hard-working, close-knit staff group, almost 50% of whom were themselves from gas-affected parts of the city, seemed to me to be well out of the ordinary. I remember that funding was so tight that year (1999) that several members of staff had, for a time, given up their salaries altogether. As they didn’t want colleagues with family dependents to suffer hardship, they took the full burden of austerity upon themselves. There was no safety-net to catch their fall. Instead, they trusted in the support they’d receive from others in turn.

There were times that Sambhavna would have struggled to keep going without sacrifices like these.

The experience of those times reinforced what was a key part of Sambhavna’s ethos from the outset: that the utmost care be taken with every single rupee. Not because money was always scarce (though often it was), but because of the belief that each penny given towards caring for Bhopal survivors is no less of a sacrifice, no less an act of trust.

Once it’s essential to a culture, trust expands in multiple directions.

Take my own story. I arrived in Bhopal with no obvious skills to offer Sambhavna’s work. Over the eight months I spent at the clinic, my most important contribution may well have been shooing away local kids keen on stripping that tall tree of its delicious, unripe mangoes. Still I was trusted to find my way to doing something useful one day.

In the photo above I’m smiling, but in truth I was anxious and wondering what on earth I was going to do without my adopted family – the photo was taken the day I had to leave.

Before reaching Bhopal again this September, the thought struck me that organisations usually start out with the best intentions. Gradually, founder members leave, compromises erode ideals, complacency sets in, and what was once a sincere enterprise for others begins to exist largely for its own sake.

At Sambhavna, something like the opposite has happened.

By 2005, support from France, Switzerland and Holland enabled the construction of a beautiful new purpose-built clinic. There is nothing else remotely like it in Bhopal: people cried when it opened. The expanded facilities made possible new areas of medical work and led staff numbers to increase by four times as many. Organisations going through such rapid growth can struggle to retain their original spirit, but as Sambhavna has grown, so has the size of its family. Today there are twice as many community health volunteers as there are staff. Trained to diagnose, prevent and even cure disease, they work across 20 communities, each giving their help freely and lovingly.

‘I work as a community volunteer in my area telling people about Sambhavna and that all treatment is free,’ explains Raïsa. ‘Often they don’t believe me or say that free care must not be very effective. Then they come and their lives change.’

For any low-income family, freedom from worry about the cost of being sick is a total blessing. In Bhopal, where gas-affected families spend on average more than a quarter of their income on medicines, free healthcare is truly a wonder, yet this is not the main reason people come to Sambhavna.

In a 2014 survey of Sambhavna visitors, by students of Banaras Hindu University, less than 10% credited ‘free treatment’ – almost nine-in-ten said their key reason for attending was ‘effective treatment’.

Of the 300 visitors interviewed, over 40% were being treated with ayurveda. Sambhavna’s guiding principle has always been ‘first do no harm’. People whose bodies are overloaded with toxic chemicals can react badly to pharmaceuticals, which are often marketed by the very same companies that make pesticides and cause environmental health problems in the first place. So while our doctors prescribe modern drugs, eg. for tuberculosis, to those who need them, they have also developed ways of combining modern medicine with traditional ayurvedic herbalism, yoga, massage and breathing exercises.

Over twenty years, Sambhavna has evolved effective non-drug treatments for asthma, diabetes, psoriasis, hypertension, pain, and menstrual complaints and is the only place in Bhopal offering free PAP smears and colposcopy.

With the help of volunteers like Raïsa, the few thousand patients registered in 1999 has grown to 32,000, but devotion to each person’s needs – a hallmark of the first clinic– remains unaffected. ‘The doctor at Sambhavna was able to understand my son’s problem and treated him with great humanity,’ the mother of one patient, Daud, told us. ‘Once he prescribed a rather expensive medicine for Daud but the Trust could not afford to pay for such an expensive medicine for long, so when Daud needed the medicine again the doctor paid for it himself. I do not have words to thank him and Sambhavna Trust.’

Those inspired by the care they’ve received often look for ways to give something back. ‘People here don’t have selfish motives’, says Santosh, a patient of several years. ‘I see that everybody is treated equally: no one is given V.I.P. treatment.’ Santosh sometimes donates to Sambhavna’s collection box. Spotting an appeal on the clinic notice board, he once brought in a clock. ‘We are never pressurised or forced to donate, we always donate as per our own will: good intentions come after seeing the work here.’

Sambhavna was an important part of local life in 1999, but over two decades it has become the axis around which a huge extended family revolves.

September’s events were a joyous celebration of this kinship and, like the best family do’s, those who couldn’t be there were celebrated just as much as those who were.

They began in a packed-out Manas Bhavan hall with exhibitions, dance, poetry, songs and speeches. One of the evening’s highlights was an uproarious, epic Kabbali by clinic staff: long-serving community health worker Aziza, a natural comic, left her family rolling with laughter in the seats next to me while a voice as melodious as a seasoned Bollywood singer flowed from librarian Shahanaz. There were sombre moments, too. Sambhavna’s epidemiological study, Dr. Jay revealed, finds that survivors of Union Carbide’s gas are developing cancers at ten times the rate of those living in unexposed parts of the city. Afflictions of the liver, throat and lung predominate.

I felt nervous the next day. 100 staff and beneficiaries were gathering together to share their stories and I needed to be a voice for thousands of supporters unable to be there. But once Sathyu had shown slides of some of the extraordinary efforts taken by people across Britain to keep the clinics alive, I didn’t need to say much. Users of both Sambhavna and Chingari stepped forward to speak. Zaid, who you may remember was only able to sit up for the first time after you paid for an operation to improve his spine, took the microphone to share his gratitude.

A cancer survivor, unable to hold back her tears, explained how Sambhavna had saved her life.

A young mother, whose son Chingari’s care had enabled to begin communicating and walking, broke down when trying to express her thanks to all of you. I replied that thanks were not needed; that friends around the world only wanted Bhopalis to have what should have been theirs by right: an adequate standard of living, access to health, medical care and a clean environment. I said that tens of thousands of small gestures, each as important as the other – collected together like drops of rain in a lake – has made 30 years of healing possible.

The final event was a spectacular show put on by the children of Chingari, and I wish you could all have been there to see it. The children performing so confidently on stage before a huge audience were facing a desperate future until you came forward to help.

‘The happiness of selfless service is greater than all happiness,’ says volunteer Raïsa. ‘In each other we find strength and joy of friendship. Yes, we are poor, but by working together we can achieve unimaginable things.’

Love,

Tim Edwards, Executive Trustee, Bhopal Medical Appeal

You can set up a direct debit or make a single gift here: CLICK

Report: 20 Years of the Sambhavna Trust Clinic – what decades of dedication and compassion has made possible

From the beginning, Bhopal survivors tried to look after their own health needs. They built their first clinic inside the grounds of Union Carbide’s death factory only months after it had gassed their families. Treatments showed promising results until armed police broke into the makeshift shanty, seized all medical records and razed it to the ground. Doctors, survivors and volunteers were beaten, arrested, and charged with outlandishly false crimes, such as attempted murder.

Ten years after the gas, Bhopal suffered in endless darkness. Other attempts to self- help had been thwarted by callous authorities, medical research programmes terminated. Families floundered under the weight of soaring medical bills, lost incomes and care of sick and dying relatives. Those who could still afford to pay were prescribed expensive, ineffective and potentially harmful steroids, pain killers, antibiotics and psychotropic medicines, many of which were banned overseas. Instead of relief from suffering, official and private medicine acted to relieve survivors of paltry compensation ‘awards’, while also increasing the chemical burden within already overloaded bodies.

Despite everything, the survivors kept struggling. They asked a team of international doctors to survey the situation. These experts called for a network of community clinics. How, though, would they be funded? We ran our first UK appeal in December 1994. With the help of friends like you, Bhopal’s survivors were finally able to create Sambhavna and begin telling of a better side of human nature, of compassion, joy, fellowship and the healing power of love.

20 YEARS OF SAMBHAVNA is a large booklet. It needed to be to explain how free, first class medical care has been dreamed of, developed and delivered to tens of thousands of survivors desperately in need of help.

The report tells us who the survivors are: where they live, what they do, their education, their income, their health experiences. We learn about the clinic’s democratic management, its treatments and results, its field workers, supporting departments, doctors, cleaners, volunteers, lab technicians, researchers, yoga therapists, medicine makers.

Their stories are also your story. Ordinary people from 45 countries have funded two decades of care at Sambhavna. Over 90% of you come from the UK.

We’d like to share these remarkable achievements with you. The 20 year report will be published later this year. If you would like to receive a copy, please contact us at [email protected] or call 01273 603278.

You can set up a direct debit or make a single gift here: CLICK

Read ‘Bhopal Matters’ a newly launched bi-annual newsletter for supporters of the Bhopal Medical Appeal here: CLICK

If you’d like to receive Bhopal Matters by post please contact: [email protected]