The International Labour Organization (ILO) was the first specialised agency of the United Nations and has a mandate to advance social justice and promote decent work by setting international labour standards. Within the UN, its tripartite structure is unique to the ILO where representatives from the government, employers and employees openly debate and create labour standards.

To mark the organisation’s centenary, the ILO the organisation released a report ‘Safety and Health at the Heart of the Future of Work’. Building on 100 Years of Experience’:

“While the road ahead presents many new challenges to safety and health at work, it is important for governments, employers and workers, and other stakeholders to seize the opportunities at hand to create a safe and healthy future of work for all. The time to take action is now”

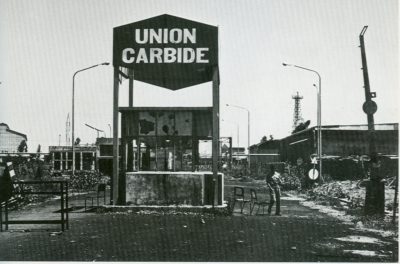

Within the report, a section on ‘Major Industrial Accidents Since 1919’ lists the 1984 Bhopal Disaster: “In 1984, at least 30 tons of methyl isocyanate (MIC) gas was released from a pesticide plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India, affecting more than 600,000 workers and nearby inhabitants. Government figures estimate that there have been 15,000 deaths as a result of the disaster over the years. Toxic material remains and thousands of survivors and their descendants have suffered from respiratory diseases and from damage to internal organs and immune systems.”

So, what a disappointment that this organisation purporting to improve social justice and working standards should underrepresent the magnitude of the disaster as it would seem to have done. The only reference is to a recent article in ‘The Atlantic’ and there is no recognition that the ‘official’ number of deaths is such a controversial and contested figure. Other organisations, including the BMA and Amnesty International, quote a figure in excess of 25,000 deaths and consider that to be a conservative estimate. Equally, the ongoing and SECOND disaster, where many tens of thousands of people have been exposed to contaminated water over an extended period, is described merely as: ‘Toxic material remains’.

What hope then for social justice and decent work standards if this is the best the International Labour Organisation can manage after a hundred years of work.

ILO Report: Safety and Health at the Heart of the Future of Work, See p.18