Saira

Saira’s story seems unique in the depth and savagery of its misfortune. But in another way it is a miracle.

How did an unwanted, unloved child, brought up in hunger, neglect and fear of beating, married off to a brute who abused her, learn to love so deeply? How did a child whose life was unfairly blighted at the age of five acquire the magnanimity to say, ‘If Dow company knew how much illness the factory is causing, it would surely help us.’ How does someone who has experienced the worst of human nature still believe in its goodness?

My name is Saîra Bi. My father Mohamed Khan Gudna Godnewalé (the tattoo artist) has lived all his 60 years in one mud hut in Chhola Naka, Bhopal. All of us children from his two marriages were born there. We were 10 brothers and sisters. Four of us are dead. One sister died before the gas disaster, another died on ‘that night’. My twin brothers died two years later. Four brothers and two sisters survive.

Our family has always been horribly poor. Besides tattooing, father massaged people with pulled muscles. The pittance he earned was gambled away. Sometimes we'd have meals, but mostly we went hungry. Our neighbours, pitying us, would sometimes send their leftovers.

Father disliked us going out. When neighbours asked, ‘Hey, Gudnaywalõ, coming to town?’ he would curtly reply that girls of our family weren’t dancing girls, but he himself never took us anywhere. Yes, I felt insulted when people called us Gudnaywalé, poking fun at us because my father was a tattooist. To them we were low caste scum. The night the gas leaked I was four and my brother was three. Our younger sister who died that night was a year old.

My memories of 'that night'

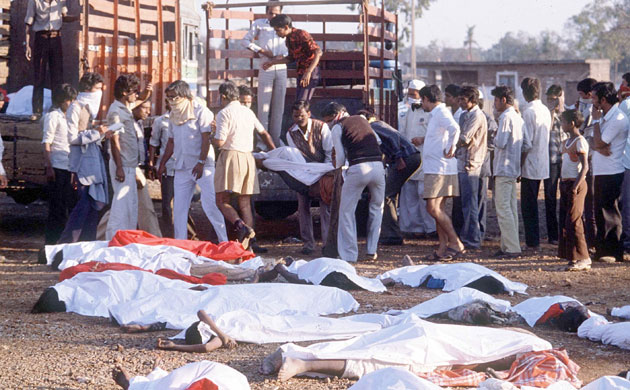

Memories of that terror will remain with me forever. My father went outside to answer a call of nature and saw people running like mad past our hut. He shouts to mother, ‘Hey, look at this! Why’s everyone running? Why are my eyes burning. What’s this smoke?’ Mother starts coughing and he says, ‘God knows what’s happening, maybe it's qayamat (the day of reckoning).’

He picked me up, put my brother on his shoulder, took my mother who had our baby sister by the hand and led us running away. It hurt to breathe, the smoke in our faces was like fire, our eyes were burning agony, like someone had thrown chili dust in them. I was choking and retching. The night was full of screams.

After stumbling some distance through lanes by the railway, our family came onto the track. There were bodies everywhere. Some people were alive but unable to move. They were coughing and vomiting, crying for help and dying. My father was gasping for breath. He couldn’t carry us any further and told my mother to take us on without him. So we became separated.

Somehow we found our way to the railway station. Thousands had gathered there. People were pouring water from pots and buckets on their relatives who had passed out to try to wake them up again, but many were already dead. My eyes swelled up so much they closed completely and I passed out. When I came to, I couldn’t see a thing but I was calling out for mother and father. Father later found us. He said he had recognised my brother by the taveez talisman we had got when we went on pilgrimage to Ajmer.

Somehow we found our way to the railway station. Thousands had gathered there. People were pouring water from pots and buckets on their relatives who had passed out to try to wake them up again, but many were already dead. My eyes swelled up so much they closed completely and I passed out. When I came to, I couldn’t see a thing but I was calling out for mother and father. Father later found us. He said he had recognised my brother by the taveez talisman we had got when we went on pilgrimage to Ajmer.

We were all taken to a hospital in Sehore town. My sister was on oxygen. Her picture appeared in a newspaper. We were given some curry sauce and bread and we children got a rasgulla each. When we got home, our berry tree had withered. Its fruits had turned black. We ate them anyway, as we were very hungry. My sister died a few months later. My twin brothers, born two years after the leak, died within ten minutes of coming into this world.

I get a new stepmother

Then my poor mother also died and there was no one left to look after us kids. Her parents worried about us. They were kind, I'd often been to their house. Mother’s brothers have a bit of farmland and they asked my father to let them take me home with them but he said he wasn’t about to start ‘distributing’ his children. Once my uncles took me off for the day. Father brought me back and gave me a hiding. Then he announced that he was remarrying and that I would never again be allowed to visit my grandparents.

Father was very happy with his new wife. When she arrived he stopped working and never gave a thought to us children. He cared only about her. We were destitute. Food was cooked once a day, and often not even once. After my stepmother had her own children they always got best of the meals. She'd give us a bit of roti and tell us to go to sleep, but would feed her own children well. If we, the first wife's children, asked for more food, we were beaten.

My stepmother beat us a lot. I often felt like killing her! I did nothing because of father. Such a bad woman, from some place near the Chambal. Dangerous, she was, did mumbo-jumbo and black magic – she struck her enemies dumb! Father was totally under her spell.

So much we children suffered. I wasn’t well. Ever since the gas, I was breathless, coughing. I went from doctor to doctor, hospital to hospital, and got no relief.

My stepmother hated me more for being ill. ‘We’ll never get rid of you. Who’ll ever want to marry a sickly creature like you? You’ll be a millstone round our necks forever.' It’s true that girls affected by Union Carbide’s gas were finding it harder to marry. So many women had miscarried and given birth to ‘monsters’. I was badly affected and thought I would never marry.

I studied up to standard II in the government girls' school in JP Nagar, where they distributed free books and cotton uniforms. My brothers got no education and father couldn't have cared less. Poor little boys, they were so hungry they searched for food in waste bins, committed thefts and petty crimes to fill their bellies. They grew up to become anti-social types, mawalis. Had my father fed them when they were little, they would not have gone astray. They were all younger than me and they were very young at the time of my marriage.

I'm married off and sent away

My father married me off to a man from Sitapur, far away near Lucknow. I was 13. My husband was a petty thug, a goon who beat up people, including me. He and my in-laws thrashed me so badly that I was passing blood in my stool. The torture was endless. I didn’t bring enough dowry, plus I was damaged goods from Bhopal. ‘You knew this,’ I said. ‘Why did you choose me?’ The last straw was my husband brought home another woman. Via an aunt I sent word to my father and stepmother asking them to bring me home to Bhopal. They replied direct to my in-laws saying that if they didn’t want me they should kill me.

The in-laws never stopped beating and tormenting me. I could not take any more. I fled in a truck driven by my aunt's son-in-law. When I got home, my father gave me a hammering and angrily took me to the station to send me back to the in-laws. On the train I was crying. A kind woman took pity on me. She brought me to an orphanage in Kallan Naar ki Gali, Ameenabad.

Three years I spent in the orphanage and learned embroidery and sewing, and even got a bit of education. Then one day the superintendent told us girls to contact our homes to be taken away. Father and his wife arrived, wept a lot, and brought me to Bhopal.

I'm nearly sold to a brothel

My stepmother soon reverted to her cruel ways. She'd thrash me violently. I had gashes on my head and deep cuts in my hands. One day she was beating my one-year old step-sister. I yanked her off by her hair and fought her. She was furious and got me tied up with rope. When my father came home, they gave me a severe thrashing.

I fled their home. A policewoman took me to Delhi and tried to sell me to a brothel. Luckily for me, a kind person intervened and brought me back to my father, but he forcibly returned me to my in-laws.

My daughter gets cancer

In all I spent nine years with my husband and his family and and bore him three children. One daughter died, two other girls are alive.

Like so many Bhopali children, the child who died developed cancer in her eye. Doctors said the eye would have to be removed or the cancer would spread to her brain. They told us to take her to Bangalore, or Kathmandu. We had no money. I said I’d try to get help in Bhopal. We came here but it was no use. When we got back my husband had run off. No one would tell me where he was. Some neighbours took pity on us and raised 10,000 rupees. A man called Furqan was trusted with taking us to a hospital in Lucknow but when we got there he vanished with the cash. The doctors asked for the money but I had none. They said that in any case it was too late. The cancer had spread to other parts.

I managed to get my girl back to the in-laws. For two months I watched her die. She was so beautiful, but her eye was bulging right out. She cried, and writhed in terrible pain. I had no money to buy painkillers for my child. Her throat swelled, choking her. She couldn't eat and became like a skeleton. Her teeth fell out. Her other eye failed. She suffered so much. One day she said to me, ‘Mama!’ and died. She was four years old.

I return to Bhopal and fall sick

After this, I brought my two surviving girls to Bhopal. The hut we live in is owned by my father. He lets us stay there. I found work as a cleaner so I could feed my daughters, but my health had worsened. I had swellings all over the body plus violent pains in my chest and spine. They never seemed to ease. My body ached. I'd get into long bouts of coughing. I found it harder and harder to breathe. From one cheap doctor to another I went, even to quacks. None could say what was wrong.

At last I was too ill to work and there was no more money. My daughters suffered a lot of hunger with me. Jeenat, she’s so young, only six, did so much for me. The water tap near our hut had run dry. She used to bring water from far away to wash my face and limbs. She'd clean the floor and wash utensils, then go out begging for food. She only went out after dark because during the day people would taunt her. One night in JP Nagar some dogs chased her and bit her leg. A rickshaw driver brought her home. She was crying and bleeding. The driver was angry with me for letting her go out alone at night. He said the dogs would have mauled and eaten her alive had he not got there in time.

I'm kicked out of hospital

My father and brother took me to the BMHRC (Note: the Bhopal Memorial Hospital & Research Centre, built from the sale of Union Carbide's impounded shares supposedly for the gas victims). The staff refused to see me without a ‘smart card' to prove I was a gas victim. I said that I had papers to show I was gas-exposed. I also had a bank book which showed I used to get £3 a month interim relief. They were at my in-laws. I said I’d send for them.

The hospital people told me to go away. My father fell at the doctor's feet but the doctor told the guard to throw us out. A doctor in the emergency unit even began abusing us. We returned home. I wrote to the in-laws but they did not send the papers. I asked again when the government distributed £300 as the first half of ‘final compensation'. They refused, saying my father would keep all the money, so I got nothing. Now a second round of £300 has been paid. Again I got nothing.

God hears my prayers

My luck changed when someone told me about the Sambhavna Clinic. My health was by then so bad that I could hardly breathe. I was in a wheelchair, but somehow got myself there. The security guard asked if I was gas-exposed. I told my story and he took me to register. Sambhavna accepted me and treated me with kindness.

Their doctor discovered that I had a damaged heart valve. It would have to be operated upon, or I would die. The doctor said that Sambhavna did not have facilities for heart surgery but he took me to see Sathyu brother, who runs the clinic. He said he’d do his best for me so I went home and prayed god to show me some kindness.

One day, I learned that god had heard my prayers. A member of Sambhavna staff collected me and took me to see a heart specialist at the BMHRC, which has facilities for surgery. Without the gas victims' smart card I had to pay, but Sambhavna bore all my costs.

BMHRC doctors agreed to admit me on condition that cash to pay for the operation and my stay was deposited in advance. These expenses were also met by Sambhavna. I was operated upon and remained in BMHRC for a month and a half. Sambhavna staff used to visit me.

I come to live at Sambhavna

Every day after my operation Diwarkar used to come from Sambhavna bringing my medicines. The first time I was in bed but couldn’t speak. Soon I was feeling a bit better and was able to talk. After I was discharged, Diwarkar brought me to Sambhavna. He said the staff had decided that until I was recovered I should stay at the clinic, because of the unhygienic conditions in our neighbourhood where sewage flows openly.

I remained at Sambhavna for a month. The staff were so friendly. They made sure I ate properly and took my medicines which I often forget to do. As my breath came back I enjoyed walking in the clinic garden. My sweet daughter, solicitious as ever, came every evening to massage my legs. I was so looking forward to being home again with my two girls.

The day I went home everyone in the clinic came to wish me well. They had collected a sum of about 2,000 rupees (£26) for me. Diwarkar used it to buy grain and other necessities for us and I also had some cash.

There are not enough words to praise Sambhavna and the treatment it provides to the poor people. It helps everybody. It saved my life. The staff of Sambhavna helped me and my children get food and shelter. Nobody does so much for others. It was my children's good luck that you people saved me. Sambhavna should be supported by all. May it earn great fame! Sambhavna is rolled-gold!

My message of hope

Nowadays I’m feeling much better. My breathing is much improved. It no longer hurts to talk. My children live in hope that one day things will take a turn for the better. Mama, don't lose the fight for life, they say. And I'm determined not to be defeated.

I want to fight my own battle. Women can do a lot. I pray to god to give me life and strength so that I can stand on my feet and not depend on others. I’ve never burdened others with my miseries, nor have I ever begged. When I was working as a domestic help, people asked me why I carried on when I was so obviously ill. It was simple. If I did not. my children would die of hunger.

Yes, I've often felt that I suffered so much because I am a woman, but to whom could I have complained? No one comes to share your sorrows. Every woman has to face hard times. Some face troubles better, some worse. But there is no point in crying in front of others. People should fight their own battles. I would like to tell every woman not to accept defeat.

Epilogue: when love is not enough

Saira Bi, aged about 27, could not survive and died on 18th April, 2008. Her daughters Jeenat and Muskan are now in the care of the Darul-Shafquat Shahjahani orphanage in Bhopal.

We publish Saira’s story in sorrow and with deep regret that despite her trust in us, we could not save her.

Everyone here at Sambhavna came to love Saira, her courage, the dignity with which she bore her terrible suffering, her humility and decency. If love alone could have saved her, she would be alive now and the writer of these words would not be in tears.

Saira's story epitomises a lot of what's wrong with the healthcare of survivors in Bhopal. Since the night of the gas leak, treatment protocols have hardly evolved. As in Saira’s case survivors are routinely prescribed drugs that do no good, and often actually harm. The gas survivors, mainly from the poorest sections of society, are often treated rudely at government hospitals. Medical records are a shambles, with little or no account taken of patient history. Some doctors won’t touch ‘lower caste’ people, so examinations are careless and perfunctory.

Saira's final weeks

When Saira left us she was stronger and eager to be back with her children. Sambhavna staff gave money to send grain, vegetables and lentils for her family. Diwarkar used go round to see Saira, take her her medicines and make sure she was taking them. At first she seemed to be doing well but slowly her condition began deteriorating. Towards the end of March she reported bad pain, cold and numbness in her legs. We took her to the BMHRC to consult the surgeon who had operated on her.

The hospital said she was imagining the pain and said that what she needed was a psychiatrist. They admitted her for observation and a week later sent her home with a report saying that doppler investigation had revealed a block in the distal portion of the descending aorta. ‘This was found to be of chronic nature,’ claimed the document, ‘and might have been present even before she was taken up (sic) for her valve surgery.’

We were unhappy with this assessment. If the aorta was blocked before surgery, how did it escape detection? Had the blockage been there before surgery Saira would have had severe pain in her legs with no femoral pulses, but she did not. The pain and coldness came afterwards. It is in fact likely that the blockage was a consequence of the surgery.

On 17th April we received word that Saira had felt very ill and had gone to the Bhopal Charitable Hospital. Biju from Sambhavna went there immediately. Saira was in intensive care. She was in a bad way, crying, groaning, screaming in pain and refusing to take any medicines. She told Biju she was sure she was dying and was worried that her children would not be looked after well after her death. Despite everything, Saira wanted to go home to her daughters. Biju called Sambhavna’s Doctor Quaiser who in turn spoke to the duty doctors at the Bhopal Charitable Hospital but Saira was too ill to go home and Biju eventually left the hospital at around half-past ten. A little after midnight we got a telephone call informing us that Saira had died.

The miracle of Saira

Next day we heard from the Shahjahani Orphanage that a woman answering Saira’s description had arrived there a few days earlier, in great pain, to ask them to care for her children. We are in constant touch, and can report that the girls are being lovingly looked after. At the recent Id festival, they had lots of presents. We will also take care of their education.

Saira’s story seems unique in the depth and savagery of its misfortune. But in another way it is a miracle. How did an unwanted, unloved child, brought up in hunger, neglect and fear of beating, married off to a brute who abused her, learn to love so deeply?

How did a child whose life was unfairly blighted at the age of five acquire the magnanimity to say, ‘If Dow company knew how much illness the factory is causing, it would surely help us.’ Sadly, this is not true, but how does someone who has experienced the worst of human nature still believe in its goodness?

We did our utmost for Saira and it wasn’t enough. What more could we have done? What could we have done better? Dozens of women like Saira are seriously ill right now in Bhopal. To help them, we need to reach them in time, and make sure they have the best available treatment. Please continue to support our work.